APA Style

Nehad Jaser Ahmed. (2025). Efficacy of Monoclonal Antibodies for Malaria Prevention: A Meta-Analysis. Clinical Pharmacy Connect, 1 (Article ID: 0006). https://doi.org/10.69709/CPC.2025.127743MLA Style

Nehad Jaser Ahmed. "Efficacy of Monoclonal Antibodies for Malaria Prevention: A Meta-Analysis". Clinical Pharmacy Connect, vol. 1, 2025, Article ID: 0006, https://doi.org/10.69709/CPC.2025.127743.Chicago Style

Nehad Jaser Ahmed. 2025. "Efficacy of Monoclonal Antibodies for Malaria Prevention: A Meta-Analysis." Clinical Pharmacy Connect 1 (2025): 0006. https://doi.org/10.69709/CPC.2025.127743.

ACCESS

Systematic Review

ACCESS

Systematic Review

Volume 1, Article ID: 2025.0006

Nehad Jaser Ahmed

n.ahmed@psau.edu.sa

Department of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Alkharj 16273, Saudi Arabia

Received: 26 Jul 2025 Accepted: 16 Nov 2025 Available Online: 17 Nov 2025 Published: 01 Dec 2025

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease caused by Plasmodium parasites. Each year, it is estimated that there are 200 to 400 million malaria cases, resulting in over 500,000 deaths. Monoclonal antibodies represent a unique strategy for long-term passive protection against malaria. This meta-analysis aims to evaluate the effectiveness of monoclonal antibody therapies in protecting against malaria. The study included clinical trials, identified through PubMed, that compared the efficacy of monoclonal antibody therapies for malaria prevention. An odds ratio (OR) was calculated using a fixed-effect model, with 95% confidence intervals, to compare the groups. The results were presented in a forest plot generated using the OR. The meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager software (version 5.4). The prevention rate in the monoclonal antibody group was 69.54%, compared to 19.02% in the control group. Monoclonal antibodies significantly prevent malaria (OR = 19.65, CI: 10.62–36.35, p-value < 0.00001). This meta-analysis underscores the promising potential of monoclonal antibodies for malaria prevention, demonstrating their capacity to provide targeted protection against Plasmodium falciparum. While monoclonal antibodies show significant efficacy, variability across populations and challenges in cost and scalability call for further research.

Plasmodium parasites cause malaria, a disease spread by mosquitoes. Plasmodium falciparum infections are the primary cause of the estimated 200 to 400 million malaria cases and over 500,000 fatalities that occur each year, most of which occur in Africa and mostly affect children [1]. The use of insecticide-treated bed nets, prompt diagnosis and treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapies, and preventive measures for high-risk populations, including pregnant women, infants, and children in seasonal malaria regions, constitute key strategies in malaria control [2]. However, due to the rise of drug-resistant parasite strains and insecticide-resistant mosquitoes, the number of malaria cases and deaths has plateaued in recent years [3,4]. Developing a highly effective vaccine to prevent malaria has long been a key public health objective. The RTS, S/AS01 vaccine (Mosquirix), which the World Health Organization (WHO) approved for widespread use in children in October 2021, offers only moderate protection against clinical malaria, with a reported efficacy of 36.3% after 4 years of follow-up. To eventually eradicate malaria, additional strategies are needed to counteract the disease’s expanding global burden and associated mortality, despite progress in vaccine development [5]. A novel method for providing long-term passive protection against malaria is the use of monoclonal antibodies [6]. By binding to the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein, a crucial mediator of infection, these antibodies have been shown to neutralize infecting sporozoites and prevent P. falciparum malaria during the pre-erythrocytic stage, which occurs before clinical blood-stage infection [7]. Passive administration of monoclonal antibodies provides a consistent level of protection. Unlike immunization, this approach does not involve variable immunological priming and is not influenced by individual differences in immunocompetence, age, or prior exposure to malaria [8,9,10]. Monoclonal antibodies targeting conserved regions of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein are also expected to be broadly effective against circulating parasite strains [11,12]. Several monoclonal antibodies generated against the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein have been isolated from malaria-free individuals, either after controlled human malaria infection or natural exposure. CIS43LS and L9LS feature leucine and serine substitutions in the functional chain region to increase serum half-life [13]. In controlled human malaria infection trials, several investigations have demonstrated that these antibodies protect against parasitemia in individuals exposed to mosquitoes carrying Plasmodium falciparum. L9LS protected the majority of participants, with complete protection observed in those who received the highest intravenous doses (5 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg). CIS43LS provided complete protection to all participants who received intravenous doses of 40 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg [13]. There is a scarcity of thorough information on the use of monoclonal antibodies for malaria prevention. As a result, it is critical to identify research gaps and investigate the potential of monoclonal antibody treatments as a viable malaria prevention method. This meta-analysis aims to assess the efficacy of monoclonal antibody treatments in protecting against malaria.

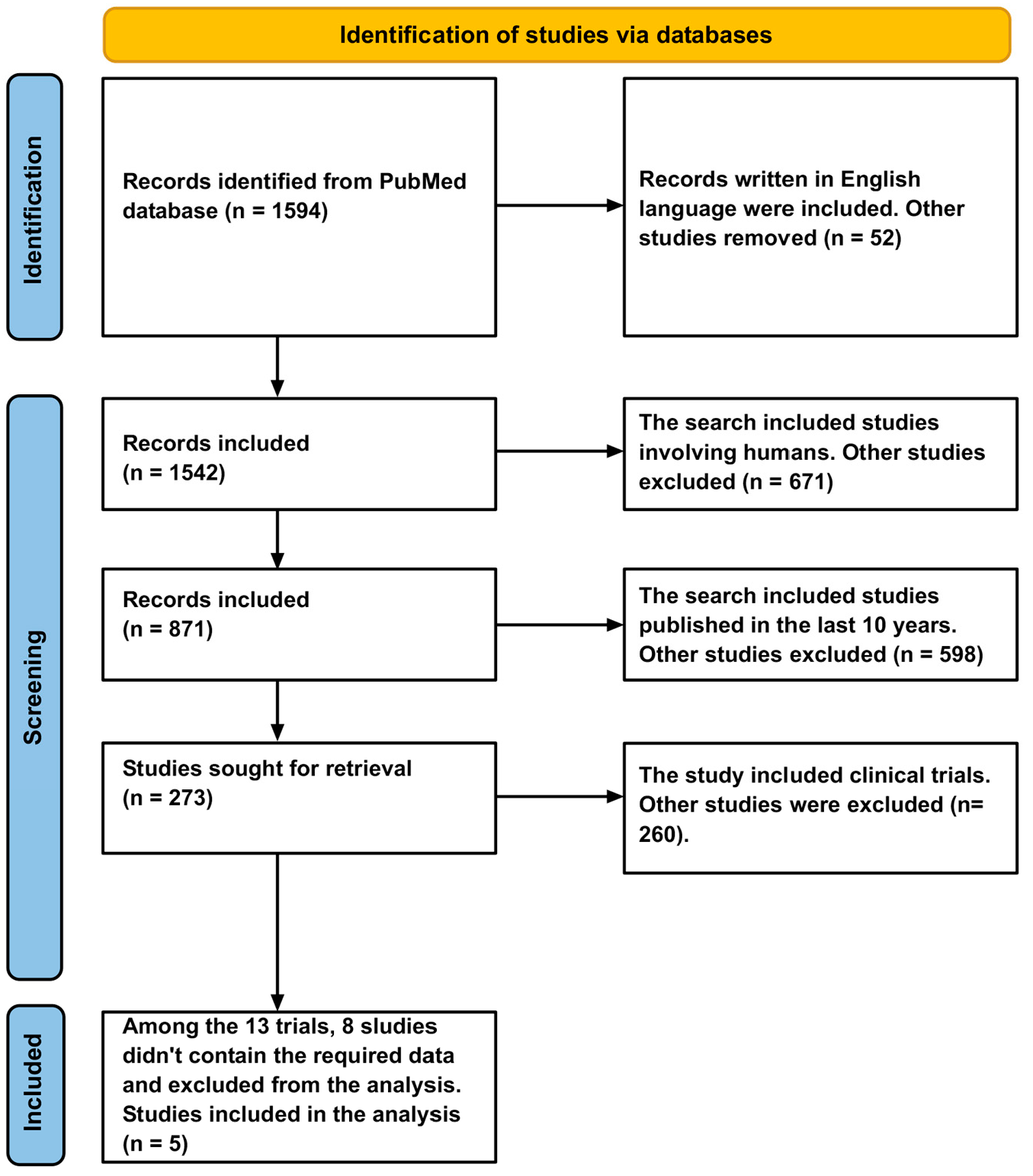

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The study eligibility criteria were defined using the PICOS framework, restricting inclusion to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the past decade that evaluated the efficacy of a prophylactic monoclonal antibody (mAb) against Plasmodium falciparum in human populations, compared to a placebo or standard of care, with the primary outcome being the incidence of malaria infection. The PubMed database was used to conduct a comprehensive literature search. Only English-language clinical trials published within the past ten years were included in the analysis. To identify additional research, the reference lists of the retrieved papers were manually screened. The study selection process was conducted in duplicate by two independent reviewers. Initially, titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility, after which the full texts of potentially relevant studies were retrieved and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through consensus or by consulting a third reviewer. The screening process, detailed in a PRISMA flow diagram, documented the number of records identified, included, and excluded at each stage. Data from the included studies were extracted using a standardized form, capturing study characteristics, participant demographics, intervention details, and primary outcome data. For the meta-analysis, the extracted data were synthesized using Review Manager software (version 5.4). The primary outcome was expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), comparing malaria incidence between the mAb and control groups. A pooled estimate was calculated using a fixed-effect model, and statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, with values of 50% or higher indicating substantial heterogeneity. The results are presented in a forest plot.

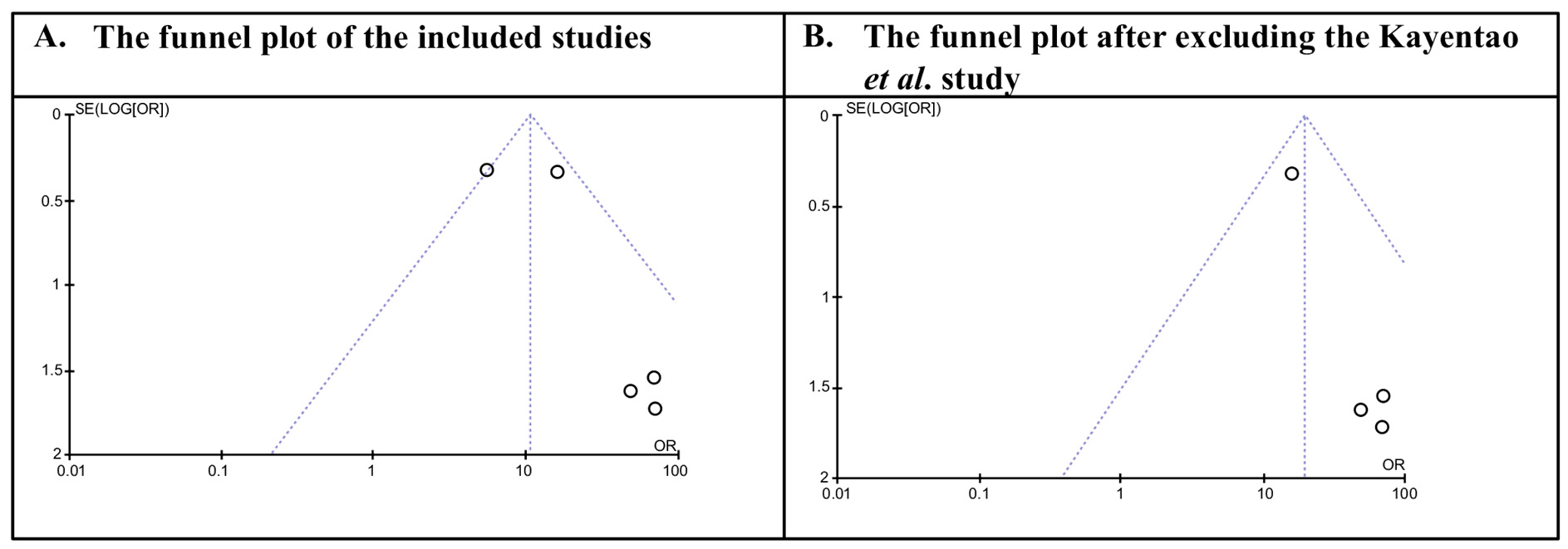

An advanced PubMed search using the terms ‘monoclonal antibody’ and ‘malaria’ yielded 1594 studies. After applying filters to include only human studies written in English, 871 studies remained. Further narrowing the search to clinical trials published within the last 10 years resulted in 13 studies. Of these, eight trials were excluded due to insufficient data, leaving five trials eligible for analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 presents a summary of the clinical trials that were included in the analysis. Among the five trials analyzed, one was published in 2024, one in 2023, two in 2022, and one in 2021 [6,13,14,15,16]. Four of these trials appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), while one was published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases. Three of the trials focused on CIS43LS, and two investigated L9LS. CIS43LS is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody developed from a stably transfected clonal cell line derived from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) DG44 cells [6]. L9LS, a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody, is manufactured in a recombinant Chinese hamster ovary cell line in accordance with current good manufacturing practices. The resulting product is a purified and formulated L9LS glycoprotein [14]. Summary of included clinical trials and their monoclonal antibodies. Table 2 presents the malaria prevention rates for the control and monoclonal antibody groups. The prevention rate in the monoclonal antibody group was 69.54%, compared to 19.02% in the control group. Malaria prevention rates in intervention and control groups. The forest plot showed that monoclonal antibodies significantly reduced the risk of malaria (OR = 10.70, 95% CI 6.83–17.74; p < 0.00001). Nonetheless, there is a heterogeneity between the studies (I2 more than 50%) (Figure 2). This variability suggests that the efficacy of mAbs may be influenced by moderating factors such as differences in participant demographics, underlying malaria transmission intensity, or the specific pharmacological properties of the different antibodies tested. Sensitivity analyses were performed by systematically excluding studies one at a time to evaluate their influence on overall heterogeneity. After the study by Kayentao et al. (2024) [16] was removed, heterogeneity decreased. Figure 3 displays the forest plot after excluding Kayentao et al. (2024) [16], revealing that monoclonal antibodies significantly reduced the risk of malaria (OR = 19.65, CI: 10.62–36.35, p-value < 0.00001) (Figure 3). The reduction in heterogeneity was also shown in Figure 4.

Study

Intervention

Control

Event

Total

Rate

Event

Total

Rate

Kayentao et al. [15]

90

110

81.81%

24

110

21.81%

Gaudinski et al. [6]

9

9

100%

1

6

16.67%

Wu et al. [14]

9

11

81.81%

0

6

0.00%

Kayentao et al. [16]

84

150

56%

14

75

18.67%

Lyke et al. [13]

18

22

81.81%

0

8

0.00%

Total

210

302

69.54%

39

205

19.02%

![Figure 2: Forest plot. This forest plot displays the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each of the five included studies (Kayentao et al. [15], Gaudinski et al. [6], Wu et al. [14], Kayentao et al. [16], Lyke et al. [13]), along with the pooled overall effect. The plot shows that monoclonal antibody administration significantly reduces the odds of developing malaria compared to the control. Significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 > 50%).](/uploads/source/articles/clinical-pharmacy-connect/2025/volume1/20250006/image002.png)

![Figure 3: Forest plot. The forest plot illustrates the results of a sensitivity analysis of the included studies (Kayentao et al. [15], Gaudinski et al. [6], Wu et al. [14], Lyke et al. [13]), conducted after excluding the study by Kayentao et al. (2024) [16]. The removal of this study resulted in a stronger pooled effect estimate and a substantial reduction in statistical heterogeneity.](/uploads/source/articles/clinical-pharmacy-connect/2025/volume1/20250006/image003.png)

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are a novel technique for providing long-term passive immunity against malaria. These antibodies can neutralize sporozoites before they reach the clinical blood stage of Plasmodium falciparum infection by targeting the pre-erythrocytic stage. This is accomplished by binding to the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP), which is important for the parasite’s capacity to initiate infection. Despite their potential, there remains a significant gap in the evidence base for the use of monoclonal antibodies for malaria prophylaxis. Addressing these gaps is critical to fully understanding their therapeutic potential and advancing their development as a viable preventive therapy. This meta-analysis aims to thoroughly assess the effectiveness of monoclonal antibody therapy in preventing malaria, thereby contributing to the growing body of evidence supporting its use in malaria control efforts. This meta-analysis highlights the potential of monoclonal antibodies as an innovative strategy for malaria prevention. By combining data from randomized controlled trials, we found that individuals receiving mAbs had significantly lower malaria incidence than those receiving placebos or routine preventive measures. The pooled efficacy estimates indicate that mAbs targeting specific malaria antigens, such as the circumsporozoite protein (CSP), are highly protective, especially in high-transmission settings. Both CIS43LS and L9LS have shown considerable efficacy in malaria prevention, indicating that they are promising monoclonal antibody-based therapies. While CIS43LS established the foundation for the use of monoclonal antibodies in malaria prophylaxis, L9LS represents an advancement, offering improved pharmacokinetic properties and potentially broader applicability. Kayentao et al. found that CIS43LS protected against Plasmodium falciparum infection across a 6-month malaria season in Mali, with no apparent safety issues [15]. Similarly, Gaudinski et al. found that CIS43LS efficiently prevented malaria in individuals with no prior history of malaria infection or vaccination, following controlled human malaria infection trials [6]. Furthermore, Lyke et al. reported that CIS43LS was safe, well-tolerated, and effective at low doses when administered subcutaneously, providing protection against P. falciparum. Their findings indicate that this monoclonal antibody may be a viable option for malaria prophylaxis across a range of clinical settings [13]. These studies, taken together, indicate CIS43LS’s potential as a safe, effective, and adaptable method for malaria prevention, particularly in endemic countries. Wu et al. and Kayentao et al. conducted research to assess the efficacy of L9LS for malaria prophylaxis. Wu et al. found that L9LS, whether injected intravenously or subcutaneously, provided substantial protection against malaria in controlled human malaria infection trials, with no apparent safety issues [14]. Similarly, Kayentao et al. found that administering L9LS subcutaneously to children gave good protection against Plasmodium falciparum infection and clinical malaria for six months. During the 28-week study period, no major adverse events occurred, and all unsolicited adverse events were mild to moderate (grade 1 or 2) and resolved on their own without requiring medical attention. These findings highlight the potential of L9LS as a safe and effective preventive strategy against malaria, especially in endemic countries [16]. Monoclonal antibodies hold the potential to revolutionize malaria prevention and therapy, as they have done for other infectious diseases. Research shows that they have the potential to target various stages of the parasite life cycle, and early human trials have produced promising results. However, considerable hurdles persist, particularly for diseases such as malaria, which disproportionately afflict low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Limited investment in research and the need for low-cost production. While technological developments can reduce production costs, the lack of funding and interest from affluent nations and donors remains a key challenge [17]. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed that monoclonal antibodies can be developed quickly, are well tolerated, and are as effective and flexible as vaccines and medications in combating infectious diseases. The high demand and profitability of monoclonal antibodies during the pandemic may stimulate further efforts to scale up manufacturing and reduce costs for other diseases, including malaria. Optimistically, these enhancements could coincide with improvements in monoclonal antibody efficacy, such as greater potency and reduced dose, to attain the required level of protection. These advances may pave the path for monoclonal antibodies to become a transformational tool in the battle against malaria [17]. The significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) observed in our meta-analysis warrants careful interpretation, as the variability in effect sizes across studies is likely attributable to clinical and methodological differences among the included trials rather than chance. Potential sources of this heterogeneity include varying levels of malaria transmission intensity across study settings, which can influence the absolute benefit of a preventive mAb, as well as population factors such as age, prior immunity, and genetic background. Furthermore, intervention characteristics, including the use of different monoclonal antibodies targeting various P. falciparum antigens, along with variations in antibody half-life, dose, and potency, and methodological differences in follow-up duration and diagnostic sensitivity, are all plausible contributors. This variability underscores that the real-world impact of mAbs will be context-dependent, suggesting that future research should aim to identify which subpopulations and settings derive the greatest benefit to guide targeted, cost-effective deployment. 4.1. Strengths and Limitations In the present study, a systematic search was conducted, quantitative data were pooled, a forest plot displaying effect sizes and confidence intervals was generated, heterogeneity was assessed, and sensitivity and publication bias analyses were performed. While the number of included studies is limited, the methodology adheres to standard meta-analytic practices. While this study has its benefits, it also has some significant shortcomings. First, although we conducted a comprehensive search, our initial strategy was limited primarily to PubMed, which may introduce selection bias and restrict the scope of included studies. Future systematic reviews should incorporate additional databases such as Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library to ensure broader coverage and minimize the risk of missing relevant trials. Second, the exclusive inclusion of published research introduces the potential for publication bias, which may affect our findings. Third, we were unable to account for differences in trial designs, patient demographics, dosing schedules, or follow-up durations, all of which potentially influence therapy effectiveness and lead to conflicting results. Furthermore, because there are presently few clinical trials on monoclonal antibodies for malaria, our findings may not apply to all scenarios. Finally, without access to individual patient data, we couldn’t delve deeper into specific subgroups for more nuanced insights. Monoclonal antibodies face significant challenges in malaria-endemic regions due to their high cost, complex manufacturing, and demanding requirements for cold-chain storage and skilled administration. These factors create major affordability and logistical barriers in the low- and middle-income countries most affected by malaria. Despite proven efficacy, their practical impact will likely be restricted by the capacities of health systems in resource-limited settings.

This meta-analysis highlights the promising potential of monoclonal antibodies for malaria prevention, demonstrating their ability to provide targeted protection against Plasmodium falciparum. While monoclonal antibodies demonstrate substantial efficacy, variability across populations and challenges related to cost and scalability underscore the need for further research. Advances in production and increased investment could enhance their feasibility, positioning mAbs as a transformative tool in reducing the global malaria burden. To realize this potential, future efforts must focus on developing sustainable implementation models, shaping policy for equitable access, and defining their specific role within existing malaria prevention strategies.

CI

Confidence Intervals

CSP

Circumsporozoite Protein

LMICs

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

mAbs

Monoclonal Antibodies

OR

Odds Ratio

RCTs

Randomized Controlled Trials

WHO

World Health Organization

The author confirms that he was solely responsible for the conception, design, analysis, interpretation, drafting, visualization, and final approval of the article.

All data generated and analyzed are included in this article.

Ethical approval and consent to participate are not required for this study, as it is based on a synthesis of existing literature and does not involve human participants, animals, or original data collection.

No consent for publication is required, as the manuscript does not involve any individual personal data, images, videos, or other materials that would necessitate consent.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

The study did not receive any external funding and was conducted using only institutional resources.

The author acknowledges the use of ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) to assist in language refinement, grammar correction, and improvement of manuscript clarity. The author reviewed and verified all content generated by the AI tool. All figures are original and have not been reproduced or adapted from previously published materials.

This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) guidelines.

[1] World Health Organization. World Malaria Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2021 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

[2] World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for Malaria. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-malaria (accessed on 25 July 2025).

[3] Ranson, H.; Lissenden, N. Insecticide Resistance in African Anopheles Mosquitoes: A Worsening Situation That Needs Urgent Action to Maintain Malaria Control. Trends Parasitol. 2016, 32, 187–196. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4] Balikagala, B.; Fukuda, N.; Ikeda, M.; Katuro, O.T.; Tachibana, S.I.; Yamauchi, M.; Opio, W.; Emoto, S.; Anywar, D.A.; Kimura, E.; et al. Evidence of Artemisinin-Resistant Malaria in Africa. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1163–1171. [CrossRef]

[5] RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership. Efficacy and Safety of RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine With or Without a Booster Dose in Infants and Children in Africa: Final Results of a Phase 3, Individually Randomised, Controlled Trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 31–45. [CrossRef]

[6] Gaudinski, M.R.; Berkowitz, N.M.; Idris, A.H.; Coates, E.E.; Holman, L.A.; Mendoza, F.; Gordon, I.J.; Plummer, S.H.; Trofymenko, O.; Hu, Z.; et al. A Monoclonal Antibody for Malaria Prevention. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 803–814. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7] Julien, J.P.; Wardemann, H. Antibodies Against Plasmodium falciparum Malaria at the molecular level. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 761–775. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8] Portugal, S.; Tipton, C.M.; Sohn, H.; Kone, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Skinner, J.; Virtaneva, K.; E Sturdevant, D.; Porcella, S.F.; et al. Malaria-Associated Atypical Memory B Cells Exhibit Markedly Reduced B Cell Receptor Signaling and Effector Function. Elife 2015, 4, e07218. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9] Jongo, S.A.; Church, L.W.P.; Mtoro, A.T.; Chakravarty, S.; Ruben, A.J.; Swanson, P.A.; Kassim, K.R.; Mpina, M.; Tumbo, A.M.; Milando, F.A.; et al. Safety and Differential Antibody and T-Cell Responses to the Plasmodium falciparum Sporozoite Malaria Vaccine, PfSPZ Vaccine, by Age in Tanzanian Adults, Adolescents, Children, and Infants. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 100, 1433–1444. [CrossRef]

[10] Oneko, M.; Steinhardt, L.C.; Yego, R.; Wiegand, R.E.; Swanson, P.A.; Kc, N.; Akach, D.; Sang, T.; Gutman, J.R.; Nzuu, E.L.; et al. Safety, Immunogenicity and Efficacy of PfSPZ Vaccine Against Malaria in Infants in Western Kenya: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1636–1645. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11] Thera, M.A.; Doumbo, O.K.; Coulibaly, D.; Laurens, M.B.; Ouattara, A.; Kone, A.K.; Guindo, A.B.; Traore, K.; Traore, I.; Kouriba, B.; et al. A Field Trial to Assess a Blood-Stage Malaria Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1004–1013. [CrossRef]

[12] Neafsey, D.E.; Juraska, M.; Bedford, T.; Benkeser, D.; Valim, C.; Griggs, A.; Lievens, M.; Abdulla, S.; Adjei, S.; Agbenyega, T.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Protective Efficacy of the RTS, S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2025–2037. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13] Lyke, K.E.; Berry, A.A.; Mason, K.; Idris, A.H.; O’Callahan, M.; Happe, M.; Strom, L.; Berkowitz, N.M.; Guech, M.; Hu, Z.; et al. Low-Dose Intravenous and Subcutaneous CIS43LS Monoclonal Antibody for Protection Against Malaria (VRC 612 Part C): A Phase 1, Adaptive Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 578–588. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[14] Wu, R.L.; Idris, A.H.; Berkowitz, N.M.; Happe, M.; Gaudinski, M.R.; Buettner, C.; Strom, L.; Awan, S.F.; Holman, L.A.; Mendoza, F.; et al. Low-Dose Subcutaneous or Intravenous Monoclonal Antibody to Prevent Malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 397–407. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15] Kayentao, K.; Ongoiba, A.; Preston, A.C.; Healy, S.A.; Doumbo, S.; Doumtabe, D.; Traore, A.; Traore, H.; Djiguiba, A.; Li, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Monoclonal Antibody Against Malaria in Mali. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1833–1842. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16] Kayentao, K.; Ongoiba, A.; Preston, A.C.; Healy, S.A.; Hu, Z.; Skinner, J. Subcutaneous Administration of a Monoclonal Antibody to Prevent Malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1549–1559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[17] Aleshnick, M.; Florez-Cuadros, M.; Martinson, T.; Wilder, B.K. Monoclonal Antibodies for Malaria Prevention. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1810–1821. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher or editors. The publisher and editors assume no responsibility for any injury or damage resulting from the use of information contained herein.

© 2025 Copyright by the Authors.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies. Learn more